Having set the context and laid the foundations of Evidence Based Practice (EBP) in the previous posts, I will now focus attention on various types of study design, what they can tell you and how to appraise them. Please see my previous post for the outline of future posts to come!

In a previous post, I referred to the definition of EBP from Sackett et al. 2000 who mentioned the importance of conscientious and judicious use of the best research evidence; this would in turn imply that as clinicians, before we use or apply evidence, we need to make a decision about the quality of that evidence (you can see where I’m going here, can’t you..)

This is where the notion of ‘Critical Appraisal’ enters the party; a very good blog post from @AdamMeakins on his website about critical thinking can be found here and deserves a read!

I think Adam makes a couple of very pertinent points – Critical Appraisal does not have to be negative and it isn’t a criticism; Critical Appraisal is an assessment of the methodological quality (Greenhalgh 2010).

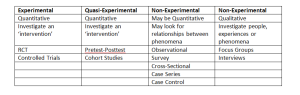

There are numerous research designs as I am sure you are very much aware! The table below (click to enlarge) shows the majority of primary research designs in a digestible format and this will be how they will be considered in future posts.

(Thank you to @NickySnowdon, Senior Lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University and Physiotherapy Research Society committee member for allowing me to kindly use her table!)

For the remainder of this post, I will be focusing on the Experimental/Quasi-Experimental study designs.

When reading a paper, it is useful to approach the article with a systematic method in order to ensure that you understand what the paper is about, and what the authors were trying to show. The suggested method that I use frequently (I think it may have been taught to me by Nicky in fact!) is as follows:

- Is this an original study?

- What was the research question and have the authors used the right study design?

- Who were the participants and how were they acquired?

- What type of methods were used, are they appropriate for the design?

- What type of analysis was used?

- Were the results interpreted logically from the method described?

Applying these questions, or keeping these questions in mind when reading the paper will help you to produce a logical critical appraisal that allows you to determine the quality of the paper you are reading.

The methods used by the researchers indicate how good the study is; don’t be fooled by the results! The critical appraisal process is essentially the means by which you establish what the researchers found and in turn how sure can you be that what they found is true.

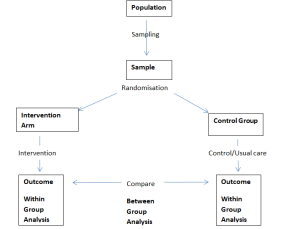

Experimental research seeks to determine the efficacy of an intervention, the gold standard design for this is the Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT); the process should look like this:

Within Group Analysis – This is where the baseline data from the participants is compared to their outcome data to determine whether any change within each respective group is statistically significant.

Between Group Analysis – This is where the data from the participants in the intervention arm is compared with the data from the participants in the control group, to see if there is any statistical significance and in turn judge the efficacy of the intervention.

Be wary of statements in papers such as this:

“There were no statistically significant differences between groups however, within group analysis of the intervention arm demonstrated a statistically significant improvement”.

I’ll break this sentence down to demonstrate how some authors attempt to ‘spin’ their results:

No statistically significant differences between groups – No difference at the end of the trial between the intervention group and the control group, the intervention can therefore be deemed ineffective.

Within group analysis of the intervention arm demonstrated a statistically significant improvement – This is essentially a quasi-experiment (see below) and therefore would only indicate that the intervention MIGHT have caused the changes seen. The presence of the control group however, would indicate that this is not the case.

If this doesn’t make sense as of yet, carry on reading and I assure you it will!

This leads me on nicely to non-experimental study designs.

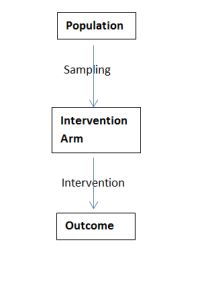

Some experimental study designs do not however include a control group – these can be seen in the second column of the table and are known as Quasi-Experimental study design; this will naturally alter the design process somewhat:

This process is typical of a pretest-posttest study; a sample of participants are measured at baseline, they all then receive the intervention being investigated before then being re-measured. Whilst this study design can show us that any change MIGHT be due to the intervention, we cannot make the conclusion that it IS the intervention that has bought about change – a control group is needed for that!

- Have the participants gone away and practiced the assessment procedures?

- Have the patients ‘regressed to the mean’?

This study design is deemed ‘Quasi’ as it isn’t a real experiment; whilst it is not possible to conclude that any change seen is due to the intervention, they do off some useful insights. Quasi-Experimental studies often act a pre-cursor to ‘real’ experimental designs and in turn may give an indication of time needed for intervention. Furthermore, whilst efficacy of the intervention is unknown, the safety of the intervention can be determined.

I haven’t portrayed it visually however, another study design to consider is that of a ‘Comparison Trial’. If you consider the RCT process outlined above, another intervention arm would be added. This is usually when the efficacy of both interventions has been established and the researcher want to determine which is more effective, how to choose between the interventions or to determine who may respond to each.

As a clinician reading a paper, it is important that your appraisal process relates to your own clinical practice – this is a bit of a bugbear of mine. Critical Appraisal tools such as those produced by CASP or seen in Cochrane papers are useful in determining methodological quality and are integral in the production of high quality review papers. However, from my own experience, I find them difficult to relate into the clinical environment.

A score of 4, 8, 9 etc. have a place in secondary review papers as they allow the reader to judge the quality of the evidence that conclusions are produced from, when it comes down to asking the ‘so what’ questions of a paper; will this work in my patients, are the results due to chance etc. These tools lack value.

So, what issues regarding methodological quality, do clinicians need to be aware of?

- How can I be sure that the results seen in these patients, will work for my patients?

- How can I be sure that the researchers haven’t biased the results?

- How can I be sure that the results seen aren’t just due to chance?

The answer to the third question is through statistics however, this is beyond the scope of this current post. I hadn’t planned to include a statistics post this year however, if the demand is there for one I am sure I can squeeze a post in looking at some basic, experimental statistics. Please leave a reply or contact me on twitter (@AndrewVCuff) if this is something you would like me to do.

In the meantime, have a look at this article from Oxford.

The first two questions relate to the sampling process and the allocation process.

Sampling – What it is and Why it occurs.

Sampling is the process by which a group of research participants are obtained from a target population, in order to be ‘studied’.

I like to keep things simple so that I can understand them; a population refers to everyone, a sample is part of that population.

The reason why sampling occurs is both theoretical and practical. In theory (and reality), the target population is going to be diverse; some people will have mild pathology, others severe pathology, different socioeconomic status, culture etc. Whilst practically, who the researcher can actually access is important.

Within sampling, the concept of validity needs to be considered. Is the sample representative of the target population? This in turn leads to the external validity of the paper, are the results generalisable to the wider population i.e. Can I use the results of this paper to guide my clinical practice? Ideally you would want the sample to include such a breadth that the results are valid to the target population as a whole.

It is through considering these factors that you determine the transferability/generalisability of the results to your clinical practice.

There are many different methods of sampling, with the method used often dependent on the aim of the research and the resources available to the researchers. Some of the main ones you may come across can be categorised into ‘Random’ and ‘Non-Random’ sampling:

Random

This method gives each person within the target population a measurable probability of been selected as part of the sample; this method is seen as the theoretical ‘gold standard’ as the representativeness of the target population within the sample is increased.

Non-random

Convenience sampling – you’ll see this a lot! It is essentially who the researchers have access to, those people near at hand (it is also cheap and easy!)

Purposive sampling – this method is dependent upon the characteristics needed to be representative of the population with the aim to obtain a sample with a particular characteristic.

E.g. Neck pain patients with experience of failed ultrasound and acupuncture.

Allocation Process

Once the sample is obtained, if there are different ‘arms’ to the study i.e. in the RCT above there was an intervention group and a control group, the sample needs to be split into the relevant groups. If there aren’t different arms to the study i.e. in the pretest-posttest study outlined above, then allocation is not required.

How can the sample be split?

Randomisation – Seen as the gold standard as it allows a cross section of variables and the groups will usually be equivalent at baseline.

Randomisation is more likely to work (i.e. produce equal groups at baseline) in a large sample (>100), not so much in a smaller sample.

Matching Pairs – More commonly used in studies with a small sample size (<50); this process attempts to equalise confounding factors e.g. height, weight, gender, baseline measurements.

When reading an RCT, this area is crucial as it can introduce a high level of bias into the study which can really undermine its findings – bias will be covered in the next post.

You need to consider whether the randomisation method was appropriate and useful i.e. was there any way that the researchers could have potentially found out the randomisation order? Ideally the randomisation should be performed ‘off-site’ and the subsequent randomisation concealed.

I usually read this section whilst considering a mental tick box:

– Was the sample randomised?

– Was this appropriate?

– Was the Method of Concealment explained?

Summary

I hope this post has allowed you to begin to understanding the critical appraisal process slightly better, or at the very least added a new dimension to your existing appraisal method. Critical appraisal is naturally an individual process, and one that will continue to evolve and develop. In the next post I will look at bias in experimental study designs.

A few tips to finish:

- If you are writing or presenting an appraisal, don’t be descriptive – set the scene but don’t go into immense detail.

- Consider the negative and positive aspects of the paper – Remember critical appraisal isn’t necessarily a criticism/negative evaluation.

- Decide whether the paper is good/moderate/poor quality and the strength of the evidence that is provides you with.

Thanks for reading guys!

A

References

GREENHALGH, T. (2010). How to READ A PAPER: the basics of evidence-based medicine. 4th ed., Oxford, BMJ Books.

Sackett, D. L., Straus, S.E., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg. W. & Haynes, R.B. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone

Pingback: Sources of Bias in Clinical Trials | Applying Criticality