As a clinician it is important to ensure that you can undertake a relative simple, but effective, literature search or at the very least, know your way around a few electronic databases!

(A more detailed understanding of the search process in research will be considered when we cover the systematic review study design and appraisal).

Literature searching is a great CPD skill and one which you will use (or should be using!) monthly for certain throughout your career. I recall receiving lectures from the Librarian as an undergraduate each year and finding them incredibly boring as she spoke in a monotone voice about truncation and Boolean operators – all foreign language before a two week cram for my dissertation! I hope that this blog post will help you formulate a literature search in a slightly less monotone manner; I don’t think anybody could make it not boring, unfortunately!

So, literature searching, looks complex and incredibly confusing when reading a large systematic review or Cochrane review, eh?

They can be complex, I’m not going to lie, but I am hoping to now give you the fundamentals with regard to finding literature to inform your practice from a clinician’s perspective.

Where will you find the literature?

A good place to start if you are still an undergraduate (or postgraduate), is the library catalogue however, from there electronic databases are your best bet e.g. Medline, Cinahl, PEDro etc.

Most of them are a much of a much in terms of how to use them and you will no doubt develop a ‘favourite’. I’m a Medline Man (wow, what a term!) but must admit I find Google Scholar incredibly useful..shameful I know.

Or is it? A recent paper by Gehanno, Rollin and Darmoni (2013) showed that if all 29 Cochrane reviews published in 2009 had only utilised Google Scholar, no references would have been missed.

Key aspects of a search strategy?

- Databases

- Keywords

- Inclusion/Exclusion for studies

- What you found in each database*

- Filtering processes i.e. how did you choose your final papers?*

*There are maybe more relevant to writing an assignment or writing up a piece of research; the first three are more applicable for the practicing clinician.

Defining the Literature Search

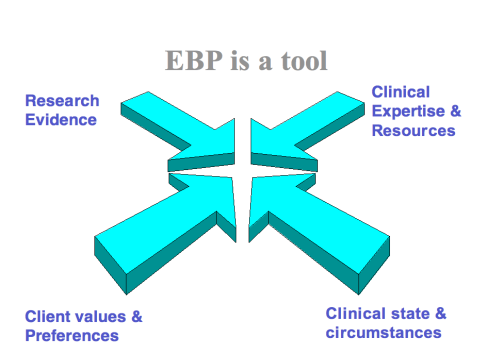

If you remember, in my previous post I presented Sackett’s definition of EBP and went on to say that an effective clinician will interpret the value or significance of research findings to theor practice i.e. individuals or specific circumstances.

You therefore need to be selective when gathering relevant literature and should consider an inclusion/exclusion criteria; this doesn’t need to be incredibly formal when searching literature to inform your practice (it’s not your dissertation after all!).

CLINICAL TIP: Inclusion/Exclusion can reduce the generalisability of findings of a paper, however, in research they are needed and are considered ‘good’ science.

A way of structuring or creating inclusion/exclusion criteria can be to draft a table, sometimes called a ‘PICO’ (Kahn et al 2011), which you may have seen used more formally in papers; it can also be used for research question formulation.

| |

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Control |

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

Population – Description of a group of participants or patients, their clinical problem and the healthcare setting.

Intervention – The main action(s) being considered.

Control – This can sometimes be a Comparison, what is the main alternative?

Outcome – The clinical changes in health state and other related changes.

Keywords

So, you know where you’re going to look and roughly what you are looking for from your search via the inclusion/exclusion criteria well, how are you going to find them? – The search strategy.

When choosing your key words to include in your search it is useful to think quite broadly, consider synonyms, different spellings, different ways of describing the same thing to help you maximise your search.

Using a table at this stage is again a great way to structure your thinking and allow your search to begin to take shape (it will also help you with using Boolean operators later on in the search process).

| |

Key Words |

| Population |

|

| Intervention |

|

| Outcome |

|

| Study Design |

|

Study Design – The appropriate ways to recruit participants or patients in a research study give them interventions and measure their outcomes.

When you have listed a few key words it can be useful to enter them into the Medical Subject Heading Terms (MeSH) vocabulary browser on the U.S. National Library of Medicine database to ensure papers that have used different terminology are included in your search (Randy and Austin 2012).

A link to the vocabulary browser can be found here: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/MBrowser.html

It also useful to consider the use of truncation at this stage; * is used to signify truncation ensuring that all possible variations of a word are identified by the search.

Truncation is used to replace letters in words, allowing you to get more results than you would with one word.

For example, you are conducting an assignment on ‘stretching’ or are wanting to look into the effectiveness of stretching within a rehabilitation programme. You could enter the word, ‘stretching’ into the database, and all the papers with that word in would return (along with a 1000 more for some reason!?).

However, if you were to truncate and enter ‘stretch*’ you would receive the papers that have included the words ‘stretch’, ‘stretches’ or ‘stretching’ (along with a 1000 more!!).

Truncation is a way of broadening your search.

I am aware that at this stage, I may be losing you with technical gumpf so please enjoy this video, it is of goats laughing like humans: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXpNdZpc7fg

So, we’ve reached the final straight whereby I introduce Boolean logic; this helps you to maximise the efficiency and efficacy of the search and appears very complex on the surface but fear not:

Let us revisit the second table:

|

Key Words |

| Population |

Athletes, Sportsman, Sports People |

| Intervention |

Stretch* |

| Outcome |

Range of Motion, ROM |

| Study Design |

Controlled Trial |

As you can see, I’ve added a few hypothetical words to aid my explanation of Boolean. If we considered each row as a group, we use the Boolean Logic word ‘OR’ within groups, for example:

Athletes OR Sportsman OR Sports People

We use the Boolean Logic word ‘AND’ between groups, for example:

Athletes OR Sportsman OR Sports People AND Stretch*

This print screen shows how these words may be added when using Pub Med (You may need to click on it to make it bigger!).

An alternative way to search the literature with Boolean logic, is to combine words with ‘OR’ as described as above however, without combining them with an ‘AND’; stay with me.

| No |

Search term (s) |

| 1 |

Valid* |

| 2 |

Back pain OR back ache OR lumbar OR lumbar spine |

| 3 |

Goniomet* OR Schober sign |

| 4 |

Range* of motion* or Assess* |

| 5 |

1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 |

So if we were searching the literature to determine which methods of measuring lumbar spine range of motion were valid we may have a search box which looks like this.

So, I’ve performed four comprehensive searches (1-4) using the ‘OR’ operator; I’ve then combined the searches not the group to give me my fifth, comprehensive search. This is the same method in theory as the one previously described however, from my experience, this second way produces a better search and is usually way seen in the literature.

Search Strategy for the Clinician – A Recap

- Utilise electronic databases.

- Use a ‘PICO’ system to draft an inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- Use a ‘PIOS’ table to draft some key words; think broadly.

- Make these key words better by using a MeSH browser and truncation (see above)

- Utilise Boolean logic to maximise the effectiveness/efficacy of your search.

- Use your inclusion/exclusion criteria to identify the papers relevant to your practice.

Phew, well that was a difficult write! I hope you ‘enjoyed it’ and you were able to take something away from reading the post even if it’s just me jogging your memories! Now that you have been able to gather a body of literature, the blog posts will now move more towards critical appraisal and various study designs.

I will attempt to get the next blog post up within the month and this will be on Critical Appraisal and Experimental/Quasi-Experimental Study Designs! I’ve managed to get the first of my guest bloggers on board who will be making an appearance over the coming months 🙂

Thanks for reading and please comment below!

A

References

Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J and Antes G (2011) Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine: how to review and apply findings of healthcare research. London: Hodder Arnold.

Randy R and Austin T (2012) Using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) to enhance PubMed search strategies for evidence-based practice in physical therapy. Physical Therapy. 92, 124-132.